The first two weeks -- developments and the strategic logic of Operation 1027 part 2 | ASPI Burma Monitor

On June 25th in Northern Shan State and Mandalay Region, the approximately 6-month long Haigeng ceasefire broke down following mutual escalation and Junta air-and-artillery strikes on rallying resistance forces between Kyaukme and Mogok. In the first fourteen days following the resumption of clashes in the area, Resistance forces - primarily the Ta’ang National Liberation Army - captured 4 military bases along with the towns of Nawnghkio and Kyaukme (a district seat), and have been able to enter other major towns of Mogok, Mongmit and the regional capital, Lashio.

In neighbouring Mandalay, the Mandalay-PDF and other affiliated resistance groups have captured a nearly-60km stretch of National Highway 31, the main road that connects the major city of Mandalay to Mogok and Kachin, and advanced towards the town of Singu on the Irrawaddy River, nearly bridging the gap between the border areas and ‘Lower Burma’.

This operation appears to have lofty goals, clearly angling to capture the city of Lashio - a major garrison city in Northern Shan State with the North-East Regional Military Command and 7 combat battalions (plus 10 more support units). The complete capture of Lashio would be the largest military defeat of the Burmese junta so far through the war (Arakan Army resistance troops are poised to also threaten the Western Military Command in the coming months). Additionally the aims appear to also be the expell Burmese Junta troops to a narrow perimetere around Mandalay City, and force them to abandon much of the surrounding countryside.

It is unfair to compare this round of clashes with the initial launch of Operation 1027 last October, since that was initially against far less well-prepared junta troops, versus the 6-months of preparation and fortification that the junta was able to undertake while the Haigeng ceasefire was in effect. But I will. Within the first two weeks of the initial Operation 1027, Three-Brotherhood-Alliance troops were able to sieze 5 towns (including 3 border posts), but no military bases. Compared to the 2 towns and 4 military bases in the first two weeks of the redux. This shows that after 3 months of combat and a 6-month break, the Three-Brotherhood Alliance is arguably more capable than they were in October, and able to capture a comprable number of strategic positions despite stronger fortifications.

The Situation Before June 25th

An approximate map of Junta-controlled territory prior to June 25th. Note that this map does not detail the large areas of mixed or contested control.

The initial Operation 1027 had sweeping impacts in North Shan State. However, despite clashes and initial early victories by the 3BHA along the road from Pyin-Oo-Lwin to Lashio (primarily around Nawnghkio and near Kyaukme), these positions did not appear to be strategic priorities for the Resistance armies and this highway was recaptured by Junta troops before the Haigeng agreement went into effect. As such, the supply and logistics chain spreading from Mandalay (Myanmar’s 2nd biggest city) to Pyin-Oo-Lwin (a core node in Myanmar’s defense academic and industrial networks) and Lashio (the headquarters of the North-Eastern Regional Command) remained largely intact, albeit obviously precariously.

Further north, the town of Mongmit was recaptured by junta forces following a brief offensive by the Kachin Independence Army against the town in late January (an offensive which likely suffered from being timed after the Haigeng agreement was signed wich allowed the junta to dedicate more resources in recapturing the town). In Mogok and despite probing raids by PDF forces, the junta remained in firm control of the Ruby mining city. TNLA troops established frontlines about 5km away from the town during Operation 1027 (and maintained a largely uncontested presence there prior to the operation), but large junta outposts set up opposite prevented them being a significant threat to the city itself.

In Mandalay, along the Irrawaddy River, the situation was similar to much of the rest of ‘lowland’ Burma, with the junta in control of almost all key towns and strategic nodes, but being unable to maintain a presence in most of the rural areas and roads connecting those nodes. (This ignores the significant but largely off-topic role of pro-Junta Pyu-Saw-Htee militias that will be the subject of a future post). Despite largely complete Resistance control in the countryside, the Resistance troops in these areas largely lacked the firepower and defensive positions to prevent concerted pushes by junta troops through their territory and existed as much more traditional insurgents than full territory-holding actors.

Despite the lull in violence during the Haigeng Ceasefire, to all actors involved it was clearly a tenuous calm. Neither the Resistance armies or the junta expected it to hold indefinetly (and I think most observers would have been shocked if it lasted a year). The Junta is not an actor known for its restraint, and the 3BHA Resistance armies clearly believed they had the upper hand in the theatre, but only signed the agreement under significant pressure from China. Accordingly, both sides were busy preparing for the rekindling of clashes.

The Junta beefed up its presence significantly in the area, establishing checkpoints and guard-posts in villages along the Pyin-Oo-Lwin to Lashio Highway. They were not all overly hardened or fortified positions, but designed to establish a sort of defense in depth, and specifically to prevent the sort of rapid gains by Resistance forces that characterised the first part of Operation 1027.

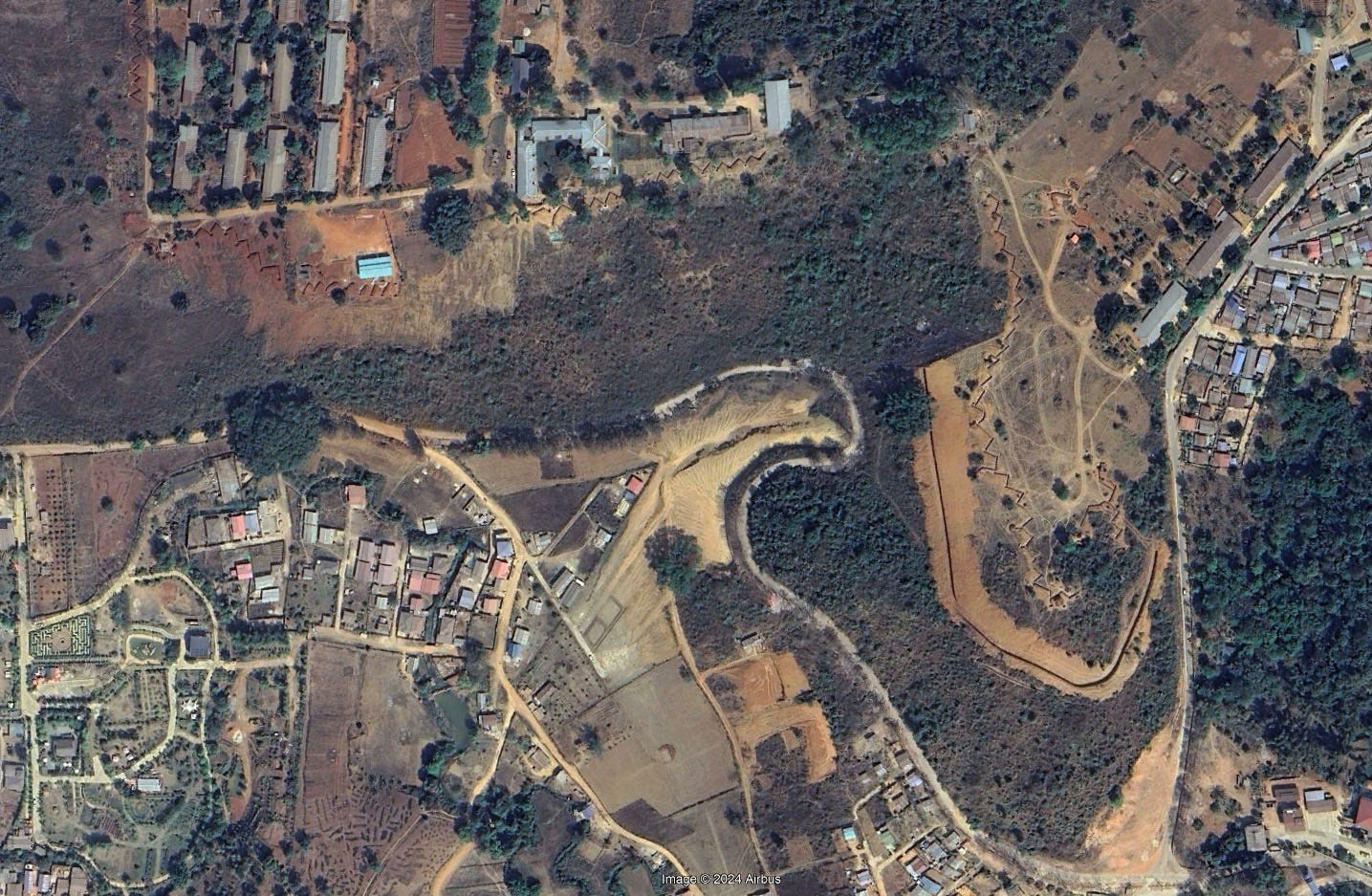

They also further fortified several key bases in the area. Prior to Operation 1027, many of these areas were considered as rear support bases, away from areas of active insurgency and were fortified accordingly. For example, most battalion bases (and other bases) in the area had doctrinal trenches dug around the staff-offices, but the bases themselves were largely defended by softer barriers such as fences or scrub. To drive this home, in April 2023, the Lashio bases of IB-40 & LIB-552 (pictured below) had fewer than 350m of dug trenches or berms - mostly as explosives protection against weapons storehouses. By March 2024, following the gains made in Operation 1027, this had basically increased 10-fold to nearly 3,000m of dug trenchs and fortifications.

This appears to be a key shift in Junta strategy that recognises the severe constraints of reinforcements and resupply that proved disasterous in the original Operation 1027 and facilitated the wholesale surrender of several units, totalling around 5,000 soldiers. There appears to be an effort to make each hardened position relatively self-sufficient.

Satellite imagery from April 2023 and March 2024 demonstrating the increase in dug fortifications.

Tactically, junta forces have adapted too, utilizing drone and anti-drone warfare much more comprehensively. Junta squads have been formally organised within many larger units dedicated to drone-bombing efforts which have been used to significant effect in clashes. Meanwhile the proliferation of drone-jamming terminals is significant and provides a meaningful barrier to Resistance efforts to soften up fortified targets before an assault (this is made more significant by the utilisation of air-power which generally only gave Resistance forces a certain time-limit to assault a position before close air support was available to the Junta).

Preparations on the side of the resistance are harder to parse. Largely because of the challenges of tracking mobile, offensive units that are not clearly telegraphed, but also because a lot of their focus has been consolidating control and establishing administrative presence in newly captured territory. There had been some reported ‘jostling’ of Resistance armies trying to occupy some of the grey-zone between frontlines, especially near major towns. The tone and action of junta troops also suggest that they were aware of significant combat preparations being made.

One relevant aspect however are the ties between the Mandalay-PDF and the TNLA that were significantly strengthened during the Haigeng ceasefire period. These ties are difficult to overstate, and it appears there was a degree of inter-operability between the two Resistance groups. The TNLA appears to have offered training, arms, safe-haven and logistics supply to the Mandalay-PDF. This coordination would prove crucial to the early successes that the Mandalay-PDF units saw in the early days of Operation Shan-Mon (this is what the NUG’s Ministry of Defence calls the offensive in Shan and Mandalay) and arguably enabled closer coordination between the TNLA and Mandalay-PDF during the launch of this offensive than even between the TNLA and other groups under the Three Brotherhood Alliance umbrella.

The Launch of Operations

In Shan State, operations initially started at around 5:30am on June 25th with the capture of junta guard-posts along the Pyin-Oo-Lwin to Nawnghkio road, clearing much of the highway and moving on to assault positions in Nawngkio and Kyaukme that day. The lightly guarded junta positions in Nawngkio town withdrew under fire and allowed the TNLA to capture the town and capture the 115th Light Infantry Battalion on the western outskirts of the town that evening.

At around 4am in the morning, Mandalay-PDF troops launched attacks around the Sedawgyi Dam and raids on junta guard-posts and reinforcements coming along the Mandalay-Mogok NH-31. By 8am, these clashes had reached the outskirts of the 1014th Air Defence Battalion stationed near the dam.

In Mogok, TNLA forces began assaulting positions overlooking the western Suburb of Kyatpyin.

On the morning of June 26th, TNLA troops were able to enter the district-seat of Kyaukme, capturing the former base of the 352nd Artillery Battalion and advancing through town towards the police station, council offices and 626th Support Platoon that afternoon. They stopped short, however, of a major assault on the sprawling 1st Military Operations Command headquarters to the northwest of the town.

Raids in Lashio township by the MNDAA would begin on the morning of June 29th in the vicinity of Nam Pawng, a rural town around 25km to the south-east of Lashio, with clashes in the city beginning a few days later on July 3rd.

The Situation after Two Weeks

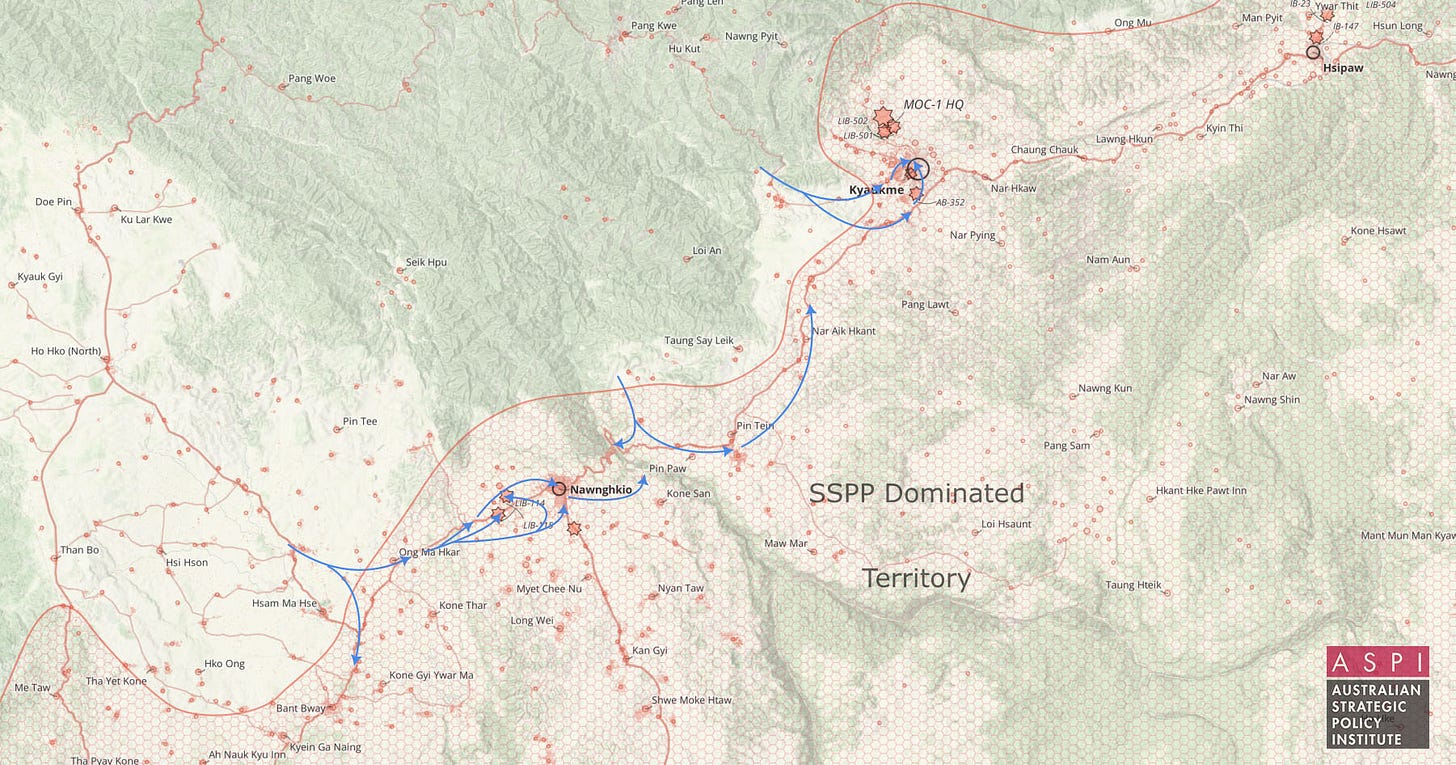

Nawnghkio and Kyaukme Township

After initial gains over the first few days in Nawnghkio and Kyaukme, the momentum slowed. There has been no consolidated offensive on the military quarter of Kyaukme (with the 1st Military Operations Command - a division-level unit, along with the 501st/502nd Light Infantry Battalions and the 912th Field Engineering Battalion). This is likely because the TNLA appears to have deployed troops that were initially assaulting Kyaukme to assist in the attack on the 606th Missiles (MLRS) Battalion, a recalcitrant base to the south of Nawnghkio which the TNLA was unable to capture over the first two weeks of assault (the base was finally captured on the night of July 10th, after 16 days of attack).

In many ways, the situation in Kyaukme is extremely similar to a previous TNLA offensive on the town of Hsenwi during the first weeks of Operation 1027. The urban area of downtown Hsenwi was captured by the group on October 29th 2023, within days of the Operation being launched. However, the military quarter of Hsenwi, with the 16th Military Operations Command and 3 combat battalions, was not assaulted, and was only captured by the Resistance troops two months later in early January.

It remains to be seen whether Kyaukme comes under a more concerted assault following the fall of the 606th Missiles Base, or whether the next step for TNLA troops is to capture junta positions towards Pyin-Oo-Lwin and further into Shan State (where further tensions with the Shan State Progressive Party would surely flare) that are currently bombarding Nawnghkio and Kyaukme with artillery, or whether they head towards Mogok.

An approximate map showing TNLA assaults into Nawnghkio and Kyaukme over the first two weeks of Operation 1027 pt. 2. Note that the arrows here are indicative and not a reflection of exact attack vectors.

Lashio

The assault on Lashio has seen a relatively slow start, with the initial MNDAA attack on the town taking place roughly a week after the TNLA attack started in Kyaukme. This perhaps indicates a lack of coordination between the two 3BHA allies. Initial clashes took place in the area of Nam Pawng, to the south-east of Lashio where several junta guard-posts in villages surrounding Nam Pawng were captured, followed by a five-day assault on the 291st Light Infantry Battalion base which was fully captured on July 5th.

The assault on the city of Lashio itself began on July 3rd, with MNDAA troops rapidly advancing to surround the town from the south and west, along with entering southern wards of the city in large numbers. The first major assault on hardened junta positions was on the 7th of July, when MNDAA troops in the 5th and 7th ward of Lashio assaulted the 507th Light Infantry Battalion headquarters from all direction, leading to limited success and the capture of outer guardposts for the base. The bulk of this assault was withdrawn following heavy bombardment overnight. A video the next day of Junta troops outside the 507th LIB demonstrated that they maintained control of the core areas of the base despite the initial assault.

According to pro-Junta media, relaying information likely discovered by the junta’s military intelligence, the bulk of the MNDAA Resistance force has not yet reached Lashio, with a major column of around 2 brigades (~2,000) troops leaving Kokang and passing through Chin-Shwe-Haw and Kunlong. According to reports this column has yet to reach Lashio. This is further information to support the theory that the continuation of Operation 1027 was unilaterally launched by the TNLA and that the MNDAA was somewhat caught flat-footed and not well positioned in the opening weeks.

There have also been skirmishes around the 902nd Field Engineer Battalion in Lashio, a support battalion in the South-Eastern outskirts of the city.

There has not been any concerted effort to capture downtown Lashio or assault key military positions in the North of the city, and MNDAA units approaching Lashio from the west have clashed with outlying guard-posts around 6-Mile (fittingly around 6-miles to the west of Lashio), but have not attempted to capture those positions or advance beyond the Lashio outer perimeter yet.

The true offensive for Lashio is not likely to begin in earnest until the MNDAA is able to assault the city with the main body of its force. However, despite these considerable reinforcements, Lashio will be a remarkably challenging fight and unlikely to fall in days or weeks, as the scale of Junta units in the town and the months of preparation specifically to defend Lashio will prevent easy victories.

In Rakhine State, on the Bangladeshi border, fellow Three-Brotherhood Alliance member the Arakan Army has employed a tactic where they isolate these major positions from supplies and reinforcements for weeks or months before beginning their frontal assault on the positions, and it is likely that Lashio will see similar attempts by the MNDAA to cause attrition among junta troops and their families (conditions for family members also under siege in other military bases has been a major contributor to the mass surrenders that we have seen) before there are widespread and intense clashes for the large Junta garrison and regional military command in the north of the city.

Gains made by the MNDAA in their assault on Lashio over the first two weeks of Operation 1027 pt 2.

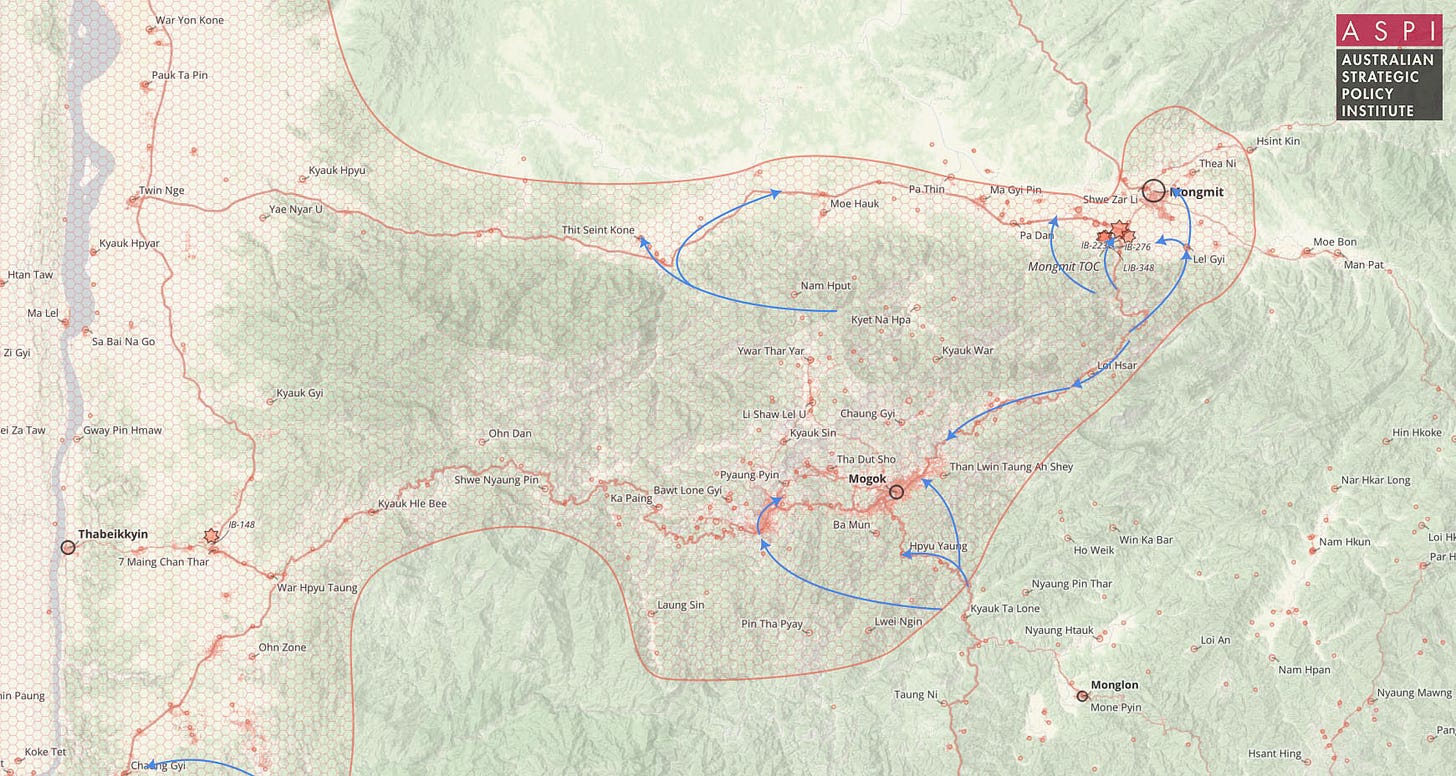

Mogok

Mogok is a large ruby-mining town on the border of Mandalay and Shan regions, with a major TNLA presence on the outskirts of the town even prior to the launching of Operation 1027 last October. Indeed, in the months prior to that operation, the most serious clashes between the Junta and the North Shan State Resistance armies were taking place around five-miles to the SE of the town.

Mogok was not immediately clear as an initial target for these latest clashes, and reporting heavily focused on the fighting near Nawnghkio and Kyaukme, but within a few days of the offensive starting, it was clear that Mogok was indeed a target.

TNLA forces initially moved to sweep through several outlying outposts that overlook the town, capturing a temporary outpost established on the grounds of a monestary overlooking the satellite town of Kyatpyin on June 26th, and siezing the town of Kyatpyin itself along with frontline bases to the south-east of Mogok the next day.

Following this, details have been remarkably unclear with many sources claiming that the TNLA is in control of large parts of western Mogok (though it is unclear to me if this is a reference to the Kyatpyin suburb or whether they have established positions within the Mogok urban areas itself). Additional footage of clashes shows that TNLA troops have also entered the south-eastern outskirts of Mogok and are making slow but steady progress down Sunrise Mountain and into the downtown area.

Mogok is not defended by any significant and hardened military bases, but the junta maintains a strong security and administrative presense in the town, which will pose challenges to an assault in urban terrain. Counterintuitively, the lack of major military bases on the outskirts of the town may make the assault on the urban area more challenging than in other locations targeted by this offensive, with Junta troops stationed in the town not having any suitable and hardened position to retreat to if they come under fire.

The TNLA has also made moves to capture highway outposts along the Mogok-Mongmit road, and appears to have largely captured that area, cutting Mogok and Mongmit off from eachother.

It does not appear that there has yet been a concerted offensive to capture the town of Mogok, with TNLA troops pushing into the city in areas without a strong Junta presence but not conducting raids on junta strongpoints within the town (note, they have attacked and captured strong-points in the satellite town of Kyatpyin). Though, I would expect Mogok to be a key objective for this phase of the offensive, and that an assault will materialise shortly.

The Situation in Mogok and Mongmit following two weeks of clashes.

Mongmit

Mongmit is a town roughly 25km to the north of Mogok, and a key town linking the Mandalay, Shan and Kachin regions of the country. Downtown Mongmit was briefly captured by the Kachin Independence Army in January, but was recaptured in a heavy Junta counteroffensive and bombardment that killed scores of civilians. The presence of the Mongmit Tactical Operations Command (a brigade-level unit) and two combat battalions makes it a relatively strong target, especially following months of effort to fortify the location.

The TNLA began attacking outer guardposts on the supply roads to Mongmit by June 30th, and had cut the road from Mogok by July 3rd. By July 7th they had began approaching the town and military bases. Over the following days the TNLA captured several guardposts, including some within 3km of the Mongmit TOC, along with establishing positions within the downtown area itself. There have been sporadic clashes with the military bases near town, but there has not yet been a major assault on these positions.

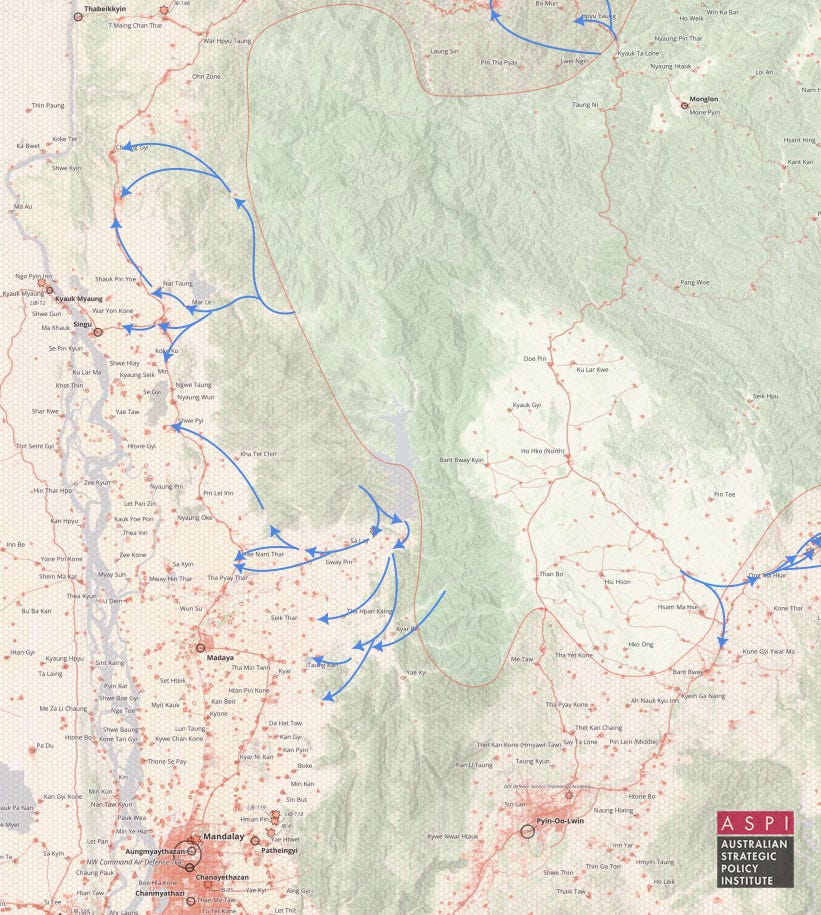

Madaya and Singu Townships

Starting on June 25th, the Mandalay People Defence Forces launched a major offensive on Junta positions in Madaya township around the Sedawgyi Dam, with their initial objective being to capture the 1014th Air Defence Battalion, 5km from the dam wall.

Following a few days of clashes this offensive was largely successful, capturing eight junta outposts by June 30th and capturing the 1014th Air Defence Battalion by July 2nd.

The Mandalay-PDF also surged south of Sedawgyi Dam and cleared several hilltop outposts within around 20km from the northern edge of Mandalay, including the Alpha Cement Plant, a sprawling industrial facility in the area and around 5km from the National Highway 31 which stretches from Mandalay to Mogok (and beyond through Mongmit into Kachin).

In early July, the Mandalay-PDF also launched assaults against Junta positions in Singu township, capturing the Marle-Nattaung Dam and the town of Letpanhla on July 3rd, and thus capturing the junction between Singu town and the NH31 highway. Five days later, on July 8th, they overrran the Shwepyi Police Station and thus had captured a roughly 60km stretch of the National Highway 31 from the Sedawygi river to the Chaungyi river near Kyitaukpauk.

There are unconfirmed reports of a brief raid on the No. 2 Military Recruitment Unit in Madaya township and only 10km from the northern edge of Mandalay city (though if these reports are true it was likely only a harassing attack rather than any genuine attempt to capture the facility).

Gains by the Mandalay-PDF in the first two weeks of the offensive, showing movements towards Madaya, Singu and cutting the NH-31.

Clashes in other areas.

Despite the above sections covering the bulk of offensive operations in Operation 1027 pt 2, there have been raids in other, rear areas of Junta control. Primarily these have been attacks to harass and disrupt the use of rear-artillery bases that the junta is using to attack the cities being captured. Clashes have taken place in Tangyan township and at the southern edge of Lashio near Mongyai.

Additionally there have been reports of infiltration attempts at Muse city along the Chinese border. Muse is certainly an eventual objective for the MNDAA, and its isolated nature would make it a far easier target than Lashio. However, its presence along the Chinese border means that clashes in Muse would likely cause high-levels of displacement along the Chinese border and would be deeply disuaded by authorities in China. The extent of Chinese pressure (and the likely unilateral nature through which the TNLA launched this offensive) has likely prevented clashes in Muse, despite Junta frontline bases being within only a few hundred metres of the city.

Strategic Developments

In the first two weeks of this operation there have been several potentially strategic developments that Resistance forces have been able to achieve, and others that have not-yet been achieved but are likely future objectives.

Firstly, the regional military centre of Lashio has been isolated from supply, troop and logistics chains in Mandalay and Pyin-Oo-Lwin. This was an objective that Junta forces fought hard to prevent during the clashes late last year - indeed the only measurable success that Junta forces had during this 3-month period was the recapturing of the Pyin-Oo-Lwin to Lashio highway. Despite months of preparation in Lashio, this now effectively seals the fate of the city, with time very much on the side of the resistance. Even failing a frontal assault on Junta positions in Lashio (and we have already seen the first lines of defence being breached in two military bases), this move will basically render Lashio as an isolated garrison in an isolated city, unable to meaningfully contribute to broader military operations and only serving in a narrow defensive role for their own garrison. As a Regional Command Headquarters, this has significant implications for the conflict in Northern Shan State. Despite the wide successes of Operation 1027, there are still 38 combat battalions under the command of the Lashio HQ and a further 18 more support units, all of which have had their chain of command effectively severed.

The next strategic development is the capture of equipment. The 1014th Air Defence Battalion in Madaya township is the first unit HQ of that type to be captured throughout the revolution. The Mandalay-PDF has been shush about what (if anything) was captured in the base when it was overran, but any equipment there is likely to pose a challenge to the use of Junta airpower and airstrikes in the theatre. Recent photos have also shown Mandalay-PDF troops with Type-74 towed anti-air guns that will likely pose a significant threat to helicopter resupply missions that the Junta army relies on in its more isolated outposts.

Most importantly, in my opinion, is the role that this offensive may have in opening more secure supply lines between the relatively arms-rich ethnic armed organisations along the border, and the PDF-resistance groups active in central Myanmar. Over the last several months it has become clear that while PDF forces in the middle of the country have the ability to overrun and capture strategic junta positions (such as their assaults on Kawlin, Taze and Tigyaing), their limiting factor has been supply. In all these cases, the PDF resistance forces have been unable to hold-out and defend the territory in the face of a significant and concerted counter-offensive by Burmese junta troops. In many cases, they have simply run out of bullets to fight with. This is where this offensive has the potential to be gamechanging. The Mandalay-PDF already exists as somewhat of a bridge between the Ethnic Resistance Organsation command and the NUG-led command that many of the ‘lowland’ resistance groups fall under. It is already effectively interoperable with the TNLA despite heavy involvement within the command chain of the NUG Ministry of Defence, and it has demonstrated throughout this offensive that the TNLA considers it an extremely close partner (arguably closer than other EROs within the 3BHA). The threat it poses to the town of Singu, and the bridge from that town over the Irrawaddy River, gives it the potential to be a literal bridge of supplies and ammo to central Burmese resistance groups ontop of its current role as a figurative bridge.

The significant successes that Karenni resistance groups and the PNLA had against junta forces earlier in the year were largely off the back of a consistent supply of weaponry and ammo. These have the potential to be echoed across Sagaing and Mandalay should supply lines between North Shan State and Sagaing (via the Mandalay PDF) be established.

After only two weeks, it is far too early to guage how the military balance in Myanmar will look following this operation’s completion, and the success of the first phase of Operation 1027 has had profound and enduring implications for conflict in Myanmar. That operation already made clear that the Junta was in clear decline (I would argue a terminal decline), and that not only was there no path for a junta victory, but that there was only a very narrow avenue to some form of stalemate. This offensive has the clear potential to close that avenue for good.

Tensions with the SSPP.

The Shan State Progressive Party or Shan State Army (North) is an Ethnic Armed Organisation with a strong presense in much of internal Northern Shan State. It has been broadly supportive of the nationwide resistance/revolution (with especially deep ties to some Resistance organisations along the Karenni border), but has not been willing to join armed resistance against the junta, focusing mainly on inter-Shan jostling.

Following the 2009 ultimatum by the Tatmadaw that all ceasefire Ethnic Armed Organisations (EAOs) be incorporated into the national Border Guard Force system, the SSPP lost several dozen outposts in many parts of North Shan State, culminating in a 2015 Tatmadaw offensive on the SSPP headquarters of Wan Hsai (this area is in the very south of my overview map at the start of this post).

As a result of this, when Junta forces began withdrawing from old-SSPP outposts in Nawnghkio and Kyaukme in the face of the TNLA assault in the area, the Shan rebel groups considered themselves to have a right to move back into their former outposts. The TNLA, meanwhile considered these bases to be the ‘spoils of war’ for their offensive in the townships, whereas the SSPP has refused to meaningfully participate in the armed resistance movement.

These disagreements had deadly consequences on July 5th when SSPP troops fired on TNLA soldiers that were approaching an outpost near Gohteik, killing 6, with minor clashes in 3 other locations.

As with most inter-rebel clashes in Burma, the violence stems from fundemental disagreements over which actors have the right to be in particular areas. There were previously clashes between the TNLA and SSPP in May, and significant tensions. However both groups have reached out to the FPNCC (Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee), a consultative coalition of EAOs in Myanmar of which both the PLSF/TNLA and SSPP/SSA-N are a member of, for mediation. The chair of this committee, the United Wa State Army, has only shown limited interest in the case, but it is far too early to determine how successful this avenue of diplomacy will be.

What is certain is that the TNLA does not want to escalate against the SSPP and vice versa, given the potential that any escalation has to spiral into costly conflict for both parties. I expect that these clashes will not escalate and that both the TNLA and SSPP (at least at the headquarters level) will show relative restraint and flexibility to limit clashes.

What to look for in the coming weeks.

In the coming weeks a lot depends on how the TNLA decides to focus its attention following the full capture of Nawnghkio, and whether they become bogged down sufficiently in their operations to be unable to help the Mandalay-PDF defend the territory they have captured along the Irrawaddy River. If the Mandalay-PDF is unable to defend this territory (and expand it into Singu town and a bridgehead across the Irrawaddy) against a concerted junta counter-offensive which - given its proximity to Mandalay and strategic importance - is almost certain to come, the strategic objectives of much of this offensive may be for naught.

We should be watching for whether the TNLA decides to attack the Military Operations Command in Kyaukme or the relatively softer target of Mogok next, and closely monitor its successes (or stallings) in these fronts. Likewise, the ability of Lashio to be defended by the junta when the main body of the MNDAA’s fighting force reaches the city will also likely be crucial to the ability of the Junta to defend across Northern Shan State, and likewise should be closely monitored.

The coming months - largely driven by events in Northern Shan and Mandalay - could prove as a crucial indicator of how long the Burmese Junta forces across several theatres in Burma can hold out against a growing and nation-wide Resistance movement.