Look towards the light: unpacking the Syrian Regime's retreat

Night-time satellite imagery reveals a key reason for the Syrian Government's combat ineffectiveness.

Simulated Night-Time light intensity along the Turkish/Syrian border between Bab al-Hawa crossing an al-Atarib

After 5 years of relative stagnation, the battle lines in Syria saw seismic shifts, upending the entire history of the revolution and war. Within two weeks of a surprise offensive, Damascus had fallen, Bashar al-Assad had fled, and Russian bases along the country’s Mediterranian coast were hurriedly withdrawing. Over 20,000 days of continuous Assad totalitarian rule came crashing down in barely more than 10.

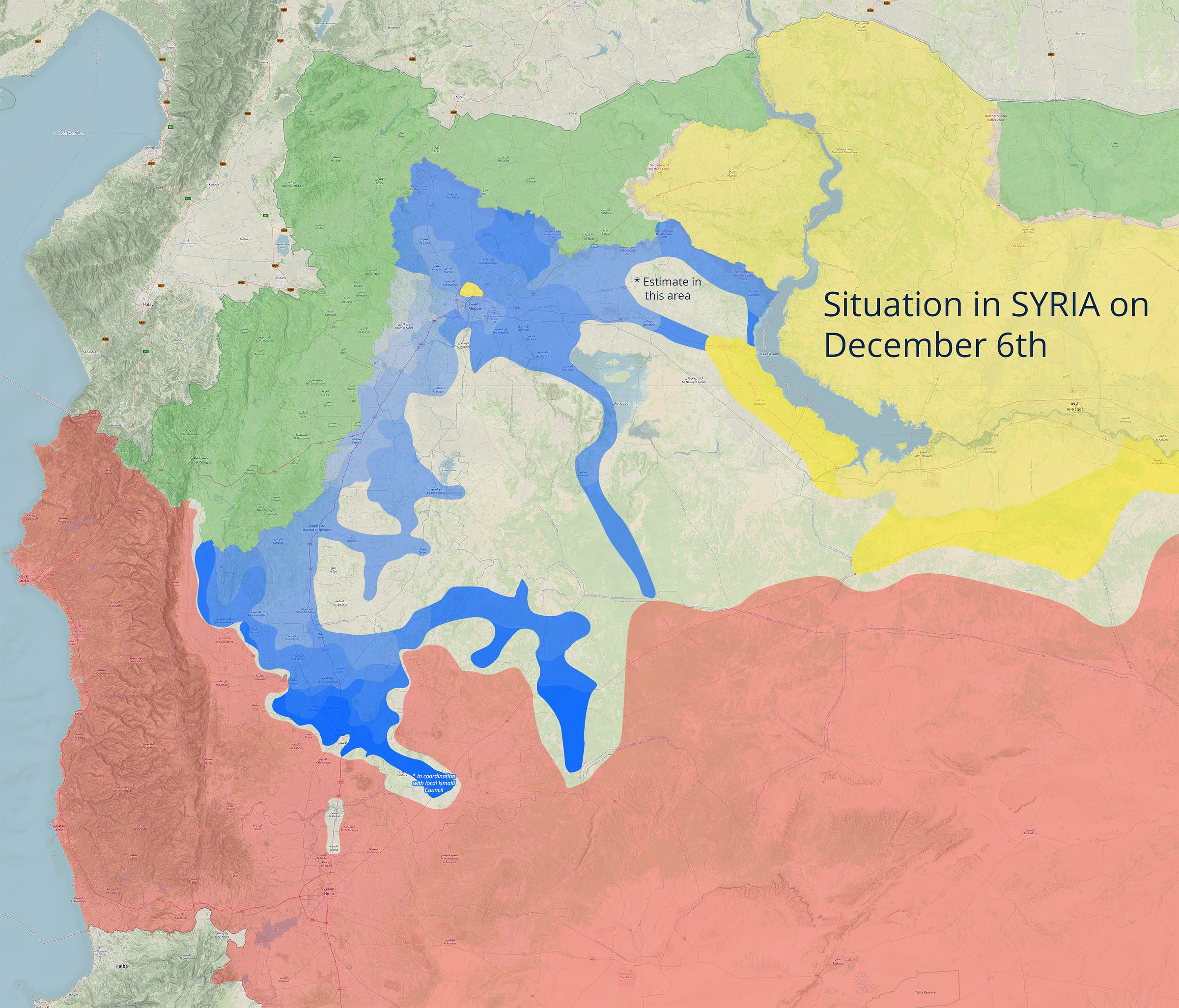

The situation across Northern Syria on December 6th. Damascus fell to the opposition on the morning of December 8th.

The groups mounting this offensive would hardly have considered this level of success. The offensive was initially launched to push back regime lines from civilian areas, where a concerted and systematic campaign of attacks on civilian areas by artillery and drones had created an unbearable burden of violence on many of the frontline communities. Instead, the regime retreated and didn’t stop. The twelve million Syrians displaced from their homes by violence and fighting are now welcome to return home.

The crucial question is why. Why and how did the regime lines collapse so quickly? Why was their command and control so poor? Why did they cede so much territory, captured over more than a decade and tens of thousands of soldier’s lives, to opposition forces within days without a fight?

A comparison between the ratio of captured and destroyed military vehicles and equipment between Russia in the Ukraine War - with heavy combat, and the Syrian Army in Syria - where equipment was mostly abandoned. Source 1, 2.

One crucial element is a distinct lack of support by foreign backers, Russia, Iran and Hezbollah, who are each embroiled in their own fights and unable to match the support for the regime that proved critical over the past ten years. Another crucial element has been the establishment of good governance by the Syrian Salvation Government and the Islamist Hayat Tahrir al-Sham which maintains firm control over much of this area. Here, the establishment of a responsive, civilian-led technocratic government has allowed for material improvements in the lives of civilians living in opposition-controlled areas. This is especially prominent following broad ceasefires that froze the front lines in Syria since 2020 and gave space for civilian institutions to re-emerge and grow despite regular attacks by regime forces.

This allowed the military factions of the opposition to rapidly professionalise, consolidate command structures and make major strides in developing new tactics and weapons (the role of drones and night-vision in the first week of this offensive was crucial in preventing Assad’s forces from regrouping and mounting counter-attacks).

These two factors explain why the regime lacked the overwhelming firepower that they were once able to bring to the battlefield with their allies’ assistance, and how the opposition was able to seize the intitative and continue to push forward beyond their initial goals. However, they don't address one critical issue that has proven decisive in battles since the offensive began; why the regime was so unwilling to fight?

A schematic showing the key factors for the Regime’s lack of combat effectiveness over the past ten days.

This article will examine that aspect.

Detailed analysis of satellite imagery captured over the previous decade begins to answer this question. Areas under regime control, despite the massive burden on loyalist communities to re-establish government control over much of Syria between 2015 and 2020, have languished since then. The demographic effects of over a decade of war and the disproportionate degree of manpower coming from traditionally loyalist and Alawite communities have sapped opportunity from these areas. The widespread economic mismanagement and lingering effects of aggressive sanctions have forced the economy in regime areas to contract.

In short, for loyalist communities around Syria, 14 years of deep sacrifice and burden has only resulted in their communities going backwards. As HTS and allied militias begin to shatter the thin veil of stability and security built up over the past 5 years where the battle lines were largely frozen, loyalist communities decided en-masse that the sacrifice was no longer worth it - especially in maintaining firm control over the large, Sunni-majority regions of Syria. The implicit social contract where loyalist sacrifices were rewarded with patronage and preferential development had languished and shattered under the pressure of an armed assault.

Since 2018, the level of night-time lights in major Regime-controlled cities across Syria has roughly halved (this is widely considered a proxy for economic activity), whereas key towns in Opposition-controlled territory have increased their night-time lights by a factor of 10. This demonstrates that despite an unending campaign of aerial bombing and economic pressure, Opposition-controlled territories, since around 2018, were able to begin to reverse the years of acute destruction and see meaningful reconstruction and revitalisation.

Indeed, in 2021, for the first time across Syria, towns hosting large numbers of internally displaced people (namely Azaz, al-Bab and the area surrounding Bab al-Hawa border crossing) became brighter than in 2012 - before the war began having large effects on the night-time lights.

A map of Syria showing how recently each area was its brightest (lighter pixels show more recent). The only parts of Syria that are most recently the brightest are Opposition-held areas near the Turkish border, the Occupied Golan Heights and areas along the Jordanian border which are artifacts of light-saturation from development in Jordan. Patches in the desert are mostly gas flares.

Meanwhile, Regime-controlled communities followed a different trajectory. Reconstruction was essentially non-existent, neighbourhoods that revolted were demolished rather than rebuilt, and even loyalist communities saw drastic reductions in livelihoods and economic opportunity.

Indeed, zooming into Regime-controlled territory specifically begins to demonstrate the increased burden that was placed on Alawite and Loyalist communities in Syria - especially during the 2014-2016 period prior to Russian intervention and which saw dramatic gains made by Opposition forces. The preferential status and patronage granted to these communities prior to the war (and this offensive in particular) is clear in the increased brightness compared in Lattakia and Tartus compared to similarly sized primarily Sunni cities (Hama and Homs). This economic and social advantage has drastically decreased since then.

SDF territory grew at a similar rate to opposition areas following the defeat of ISIS before stagnating under Turkish airstrikes which systematically targeted power infrastructure.

The observed trend in night-time light intensity between 2020 and 2024, with blue showing increases and red showing decreases.

The contrast is also clear in population estimates, with the percentage of Syrians (in-country) living in Opposition-governed territory growing between 2020 and 2023, according to analysis by the Jusoor Center for Studies, from 24% to 26% despite systematic bombardment and violence by the Assad Regime.

Likewise, the effects of economic mismanagement and sanctions in government-controlled Syrian territory are clear in the shortages of basic goods over the last 4 years, the sweeping cutting of government subsidies and the dramatic devaluation of the Syrian Pound. For example, since 2020 there have been acute fuel shortages across Government-held territory, which have worsened in recent months, over that same time the value of the Syrian Pound has fallen from 2,000/USD to under 15,000/USD. The price of bread and other stable goods had also drastically risen.

The battlefield effects of these dynamics were clear as soon as this shock-offensive was launched, with frontline units melting away and - for example - the fortified but undermanned 46th Regiment HQ falling to Opposition fighters in the first day. As early as November 28th, there were widespread reports of soldiers from the loyalist coastal communities deserting the Aleppo, Idlib and Hama frontlines to return home.

As the Opposition offensive swept through Aleppo and kept pushing south, fighters came up against the Hama ‘minority-wall’. This is a collection of Christian and Alawite villages in Hama and Homs that had previously been mobilised by the Syrian Army to effectively defend the frontlines in this area from Opposition assaults. While some of these villages - with the assistance of Syrian army reinforcements - put up a fierce defence of particular localities to the north of Hama, most of these villages were captured without fighting and often with hyper-local agreements. Such agreements saw the non-violent capture of both the Ismaili city of Salamiyah and the Christian town of Muhrahda on the outskirts of Hama by the opposition. This experience sharply contrasts previous attempts at Opposition outreach in these areas. It demonstrates both the increased local confidence in Opposition governance and the languishing conditions in Regime territory - not to mention the changing reality of the war. This has now even occurred in Assad’s hometown.

In the days following the fall of Assad’s government, there was an outpouring of grievances and complaints about the final years of his rule, even from outright Regime cheerleaders, who now felt comfortable articulating the deep issues of Assad’s rule. Bashar al-Assad’s sister-in-law posted a picture of the revolutionary Syrian flag on Instagram.

While the rest of the world saw Syria as a ‘frozen-conflict’, Assad and his regime’s poor governance were hollowing out state capacity and institutions, building resentment and the lives of its people were only getting materially worse. Under the threat of a competent and concerted Opposition offensive and without the support of foreign militaries to help it fight-back more easily, Syrians pushed through this shell and emerged under a revolutionary flag.

What software did you use to calcuate the light-levels?

One conclusion from all this could be that sanctions were an important part of the reason for Al-Asad's fall. Do you have any view on that?

Opposition-held Idlib fell under the sanctions too. But perhaps it was impacted less due to being de facto more integrated with Turkey for import purposes?

Another counter-argument would be that, per Haid Haid and others, the most important public good that the rebel authorities provided was security and justice. That could explain migration into rebel areas and the willingness of minority villages to defect, but not the lights.

Or perhaps the impact of the sanctions was minimal compared to the venality and corruption of the Asad regime?